Nick Dyrenfurth

Executive Director of the John Curtin Research Centre

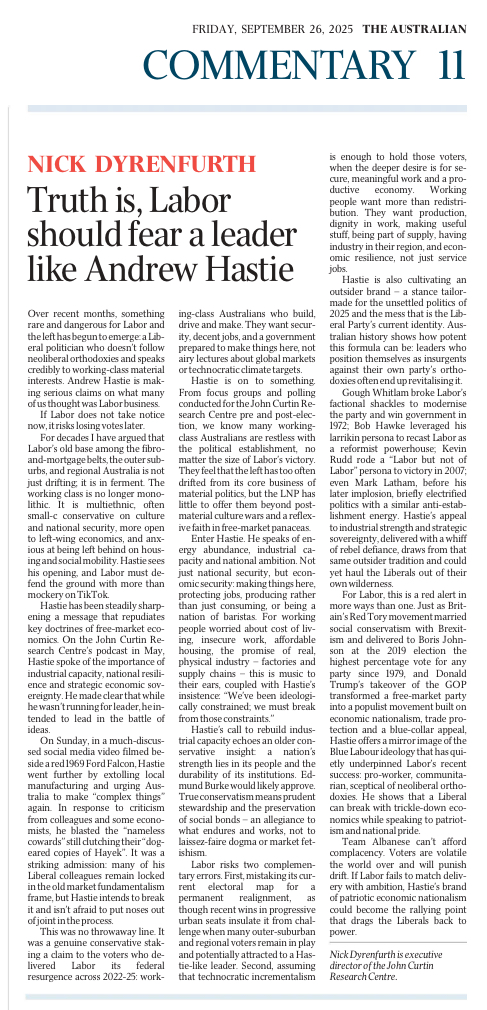

Over recent months, something rare and dangerous for Labor and the left has begun to emerge: a Liberal politician who doesn’t follow neoliberal orthodoxies and speaks credibly to working-class material interests. Andrew Hastie is making serious claims on what many of us thought was Labor business.

If Labor does not take notice now, it risks losing votes later.

For decades I have argued that Labor’s old base among the fibro-and-mortgage belts, the outer suburbs, and regional Australia is not just drifting; it is in ferment. The working class is no longer monolithic. It is multiethnic, often small-c conservative on culture and national security, more open to left-wing economics, and anxious at being left behind on housing and social mobility. Hastie sees his opening, and Labor must defend the ground with more than mockery on TikTok.

Hastie has been steadily sharpening a message that repudiates key doctrines of free-market economics. On the John Curtin Research Centre’s podcast in May, Hastie spoke of the importance of industrial capacity, national resilience and strategic economic sovereignty.

He made clear that while he wasn’t running for leader, he intended to lead in the battle of ideas.

On Sunday, in a much-discussed social media video filmed beside a red 1969 Ford Falcon, Hastie went further by extolling local manufacturing and urging Australia to make “complex things” again. In response to criticism from colleagues and some economists, he blasted the “nameless cowards” still clutching their “dog-eared copies of Hayek”. It was a striking admission: many of his Liberal colleagues remain locked in the old market fundamentalism frame, but Hastie intends to break it and isn’t afraid to put noses out of joint in the process.

This was no throwaway line. It was a genuine conservative staking a claim to the voters who delivered Labor its federal resurgence across 2022-25: working-class Australians who build, drive and make. They want security, decent jobs, and a government prepared to make things here, not airy lectures about global markets or technocratic climate targets.

Hastie is on to something. From focus groups and polling conducted for the John Curtin Research Centre pre and post-election, we know many working-class Australians are restless with the political establishment, no matter the size of Labor’s victory. They feel that the left has too often drifted from its core business of material politics, but the LNP has little to offer them beyond post-material culture wars and a reflexive faith in free-market panaceas.

Enter Hastie. He speaks of energy abundance, industrial capacity and national ambition. Not just national security, but economic security: making things here, protecting jobs, producing rather than just consuming, or being a nation of baristas. For working people worried about cost of living, insecure work, affordable housing, the promise of real, physical industry – factories and supply chains – this is music to their ears, coupled with Hastie’s insistence: “We’ve been ideologically constrained; we must break from those constraints.”

Hastie’s call to rebuild industrial capacity echoes an older conservative insight: a nation’s strength lies in its people and the durability of its institutions. Edmund Burke would likely approve. True conservatism means prudent stewardship and the preservation of social bonds – an allegiance to what endures and works, not to laissez-faire dogma or market fetishism.

Labor risks two complementary errors. First, mistaking its current electoral map for a permanent realignment, as though recent wins in progressive urban seats insulate it from challenge when many outer-suburban and regional voters remain in play and potentially attracted to a Hastie-like leader.

Second, assuming that technocratic incrementalism is enough to hold those voters, when the deeper desire is for secure, meaningful work and a productive economy. Working people want more than redistribution. They want production, dignity in work, making useful stuff, being part of supply, having industry in their region, and economic resilience, not just service jobs.

Hastie is also cultivating an outsider brand – a stance tailor-made for the unsettled politics of 2025 and the mess that is the Liberal Party’s current identity. Australian history shows how potent this formula can be: leaders who position themselves as insurgents against their own party’s orthodoxies often end up revitalising it.

Gough Whitlam broke Labor’s factional shackles to modernise the party and win government in 1972; Bob Hawke leveraged his larrikin persona to recast Labor as a reformist powerhouse; Kevin Rudd rode a “Labor but not of Labor” persona to victory in 2007; even Mark Latham, before his later implosion, briefly electrified politics with a similar anti-establishment energy. Hastie’s appeal to industrial strength and strategic sovereignty, delivered with a whiff of rebel defiance, draws from that same outsider tradition and could yet haul the Liberals out of their own wilderness.

But the Latham experiment also offers a warning: permanent opposition to your own party is a lonely and unsustainable position, and veering too far right – into Jacinta Nampijinpa Price territory on migration – which risks alienating the centre; a true Burkean knows that prudence, especially on issues like the environment, is the essence of conservatism.

For Labor, this is a red alert in more ways than one. Just as Britain’s Red Tory movement married social conservatism with Brexitism and delivered to Boris Johnson at the 2019 election the highest percentage vote for any party since 1979, and Donald Trump’s takeover of the GOP transformed a free-market party into a populist movement built on economic nationalism, trade protection and a blue-collar appeal, Hastie offers a mirror image of the Blue Labour ideology that has quietly underpinned Labor’s recent success: pro-worker, communitarian, sceptical of neoliberal orthodoxies. He shows that a Liberal can break with trickle-down economics while speaking to patriotism and national pride.

Team Albanese can’t afford complacency. Voters are volatile the world over and will punish drift. If Labor fails to match delivery with ambition, Hastie’s brand of patriotic economic nationalism could become the rallying point that drags the Liberals back to power.