Detained at his majesty’s pleasure was not on John Curtin’s 1916 bingo card.

Then Labor prime minister Billy Hughes’ call-up of single men for military training ensnared Curtin, a leading opponent of his conscription for overseas service plebiscite. Under the War Precautions Act, Curtin was charged with failing to enlist. Convicted to three months jail, he served just three days.

Aged 31, the future Labor leader had good reason not to view his future in Panglossian terms. Conscription seemed destined to win an overwhelming ‘Yes’ vote. The World War One ALP government effectively split, exiling Labor from power nationally for 13 years.

Appointed as organiser of the anti-conscription campaign, Curtin was facing his own demons. According to David Day’s magisterial biography, despite “operating with the energy of a tornado”, his battle with the bottle, and stress of work and war, knocked him flat.

Victorian Labor MP Frank Anstey wrote to his convalescing friend Curtin in July 1916. His comrades, Anstey wrote, would be “delighted to see you climb out reborn”. “Stand upright, proud of yourself, proud of the conquest that you are going to achieve and the good that you will yet do”. Curtin defeated conscription, twice. He beat the booze. In 1935, he won the federal Labor leadership by a single caucus ballot.

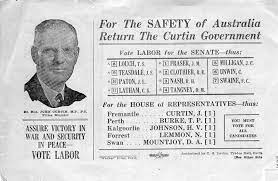

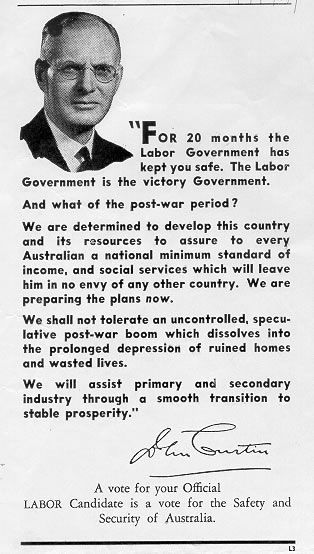

Twenty-five years on from his jailing, Curtin was remarkably sworn in as Australia’s 14th prime minister in October 1941.He remains the sole West Australian-based PM, and only one jailed. Curtin not only lead the country through the trials of World War Two but with Treasurer and successor Ben Chifley conceived of a bold postwar reconstruction agenda – full employment and intervening as necessary through Keynesian economics. It inspired Labor’s 1943 election motto of “Victory in war, victory in peace.”

Eighty years to this day arrived Curtin’s finest moment – the 21 August 1943 election. Claiming it had won the ‘Battle of Australia’, Curtin won a landslide victory – Labor’s greatest-ever – winning two-thirds of House of Representatives seats on a two-party preferred vote of 58%. The Coalition won just 19 seats. In the words of one journalist, the opposition was left dazed “in a Curtin-made opium dream”. “A new world is being created today by the terrific struggle in which we are engaged,” Curtin told Australians shortly afterwards, “better than the one we knew, with its recurring wars, grievous sacrifices, economic depression and widespread want.” Tragically, Curtin did not live to see this dream realised, dying in July 1945, “a war casualty if ever there was one”.

What can be learnt from Curtin’s triumph? First, impotent opposition is no substitute for winning and making the most of office – “we are not here for mere gestures was the message Prime Minister Anthony Albanese delivered to delegates at this weekend’s ALP national conference” – a hard lesson the one-time radical Curtin had to learn and in turn teach his colleagues. He governed for only four years but changed Australia forever – prosecuting a successful war effort while maintaining social cohesion, instigating bold economic and social reform, and reconceptualising our place in the world.

Second, are salutary lessons for the beleaguered ‘Yes’ Voice campaign. Perhaps the Curtin government’s major disappointment was its plan to secure increased powers for the Commonwealth by constitutional amendment in 1944. The ‘14 points’ referendum would have extended government control of the economy and other aspects of life for five years after the war. Lacking bipartisan support, it lost the national vote and failed to carry a majority of states. Referendums are hard to win and easier to defeat.

Finally, the Liberals might, paradoxically, have most to learn. Curtin’s triumph owed as much to his personal popularity and incumbency as the moribund United Australia-Country Party opposition of Arthur Fadden and octogenarian Hughes. They had little to offer a population whose expectations of the expanded role of government were transformed by total war.

Likewise, the Coalition is struggling to articulate an alternative vision of Australia in the mid-2020s, one reshaped by the pandemic and insecurity at home and abroad. The centre-right is on the nose with young voters, women, and migrant voters, notably in its former ‘Jewel in the Crown’, Victoria. Out of office in every state and territory except for Tasmania, and losing blue-ribbon seats to Labor, Greens and Teals, it is defined by its negativity. Defeating the Voice is unlikely to translate into electoral success.

The nadir of 1943 inspired Robert Menzies to unite the fractious non-Labor forces. The modern Liberal party was born of “a liberal and progressive faith”, according to Menzies, the antithesis of a “party of reaction.” His appeal to the ‘Forgotten People’ resonated with ‘moral’ middle-class Australians defined by more than mere materialism. Today, the same voters are deserting the Liberals. It is hard to see Generation X, Y and Z returning to a party which offers them little prospect of home ownership as per Menzies, is unconcerned with rising inequality and hostile to climate action, none of which ought to be alien to mainstream ‘small c’ conservatism. Yet the Coalition’s guiding philosophy is schizophrenic: ‘big C’ conservatism meets loopy libertarianism.

The Coalition lacks pragmatism and agility. Menzies, who became PM for a second time by defeating Chifley in 1949 ushering in 23 years of Liberal rule, largely accepted the postwar economic consensus, despite his spicy ‘antisocialist’ rhetoric. In 2023, it is difficult to conceive of Peter Dutton or another leader recognising that Australia has moved on from a pre-pandemic and even pre-GFC political framework. Warning signs were there following John Howard’s defeat in 2007. Yet as internal ructions gripped the Rudd and Gillard governments, the Liberals deferred renewal.

They can defer no longer, for their own good and that of our democracy.

Nick Dyrenfurth is Executive Director of the John Curtin Research Centre